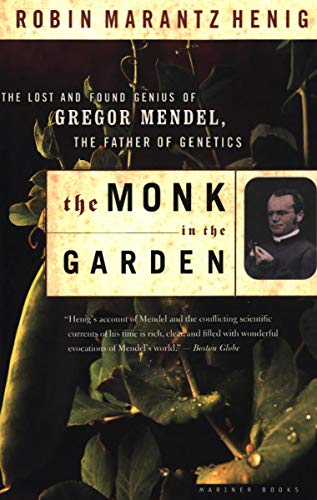

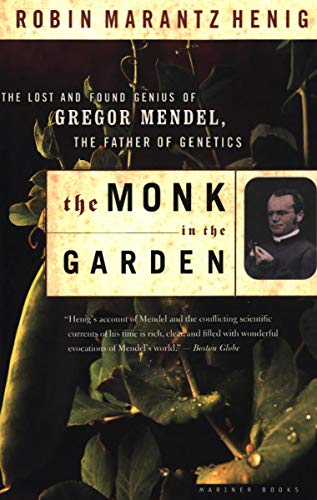

Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel

by Robin Marantz Henig

The first ever biography written about Johann Gregor Mendel, the father of Genetics, was “Life of Mendel” by the revered biologist Hugo Iltis who was also one of the people behind the establishment of the Mendel Museum in Brno. The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, is not another biography of the father of Genetics, it is an exquisitely meticulous account of events leading to the origin of the field of Genetics and the establishment of the Mendelian legacy. By force of habit, I endeavour to read between the lines while I’m engrossed in the book, trying to deduce what the author’s thoughts must be while writing the book. I failed miserably in doing so while reading ‘The Monk in the Garden’ because I had found another subject who piqued my interest more than the author – Johann Gregor Mendel.

The author of this book, Robin Marantz Henig is a writer who works as a freelance science author with multiple publications accredited to her name. With this book, she strives to bring forth the holistic details of the contributions of several people who made the Mendelian Genetics possible. This account was important, as addressed by the author, because even geniuses like Gregor Mendel need the favourable environment, factors, and people for them and their science to reach the deserved recognition.

The author mentions that Johann Gregor Mendel was from a farmer family. His father expected him to take over the lands and farming, but Gregor, then Johann, was a bright student who used to go to the Gymnasium to study and thus wanted to pursue his passion of the study of the natural sciences. Had his sister not given up her dowry money to Johann for further studies, he might have gotten stuck in maintaining his father’s legacy rather than building his own. Even after that, Johann had limited resources at hand to pursue his passion. He therefore joined an Augustinian Church that famously encouraged its monks and members to study and took exceptional pride in it. It is here in St. Thomas’ Abbey that Johann was Christened to be called Gregor. As a natural science student and enthusiast, Gregor Mendel studied Biology, Meteorology, Mathematics, and had special interest towards Physics. With tribulations, he was able to study Physics from the University of Vienna and then ultimately become a teacher and tutor the subject in his Abbey.

He was an avid and scrupulous record keeper. Everything that Mendel observed, according to him, could be data that could be statistically grouped. He did the same with his hobbies of Meteorology, bee keeping, and rat breeding. Gregor originally wanted to experiment on rats, however due to rigid rules against animal breeding in the monastery, he had to shift his experiments to plants whilst rekindling his love for gardening. Experiments on Pisum sativum were not easy. Mendel had to wake up early in the morning during winters to conduct his plant breeding experiments. This was in addition to the mundane and rigorous harvesting and tallying of each experimental pea and peapod. All this work seems almost mechanical and tedious, and Gregor Mendel continued it for 7 years before he published his findings in 1865.

Mendel’s presentation of his work at meetings and conferences seemed to be futile because his peers were unable to understand the maths behind the work and the inference that Mendel was getting at. From almost all his peers, he experienced rejection for review and recognition, especially one of the famous biologists of the time, Carl von Nägeli. Mendel tried everything in his power to get into correspondence with Carl von Nägeli and succeeded after he proposed a collaborative work in Hieracium breeding, which was one of Nägeli’s leading interests. They wanted to pick out patterns in Hieracium breeding and understand its inheritance like Mendel did with Pisum. This, however, became the undoing of Mendel because Hieracium majorly reproduces through apomixis i.e., asexual reproduction. Thus, Mendel could not replicate the Pisum results in Hieracium and lost confidence in all his years of plant breeding work. As a consequence of this, along with his shift in life priorities, he stopped reprinting his paper thereafter and his work was “lost”.

The book details the perseverance of William Bateson, another renowned biologist and the person who coined the term “Genetics”, in establishing Gregor Mendel as the father of Genetics and ensuring that genius in his work received the recognition it deserved. The author also talks about the rediscovery of the Mendelian Laws of Inheritance by Carl Correns, Hugo de Vries, and Erich von Tschermack in 1900. With these instances and stories of Mendel, the author emphasises the need for solidarity in the scientific community. She stresses upon the importance of support from family, friends, and peers for one’s achievements. Moreover, she highlights the qualities of genius in Gregor Mendel which aptly acclaim him to be the Father of Genetics. The author ends with the mention of the legacy of “Mendelian Genetics”; how genes, chromosomes, DNA, cloning, and genetic modification came to be in the post-Mendelian era. The book was written in the late 20th century and published in 2000, thus lacking the perspectives of the impact of the Mendelian Genetics on the post-Human Genome Project era.

Note: This "review" is not a book review in its conventional sense. Rather, I wrote it as an echo of the book "The Monk in the Garden". Here, I give a detailed account of a few important points in Mendel's life, to spread the word of inspiration and motivation amongst my fellow colleagues, as the book did for me.

Srashti Jyoti Agrawal, PhD researcher in Dr. Sridhar Sivasubbu’s lab, is studying the powerhouse of the cell with the help of little friends called Zebrafish. She is a part-time reader who gets thrilled by mysteries.

She is an art and writing enthusiast who loves to explore new things.